HISTORY PART ONE

Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Copyright © 1998, 2021 @149st. All rights reserved.

GROUNDWORK 1966-71

Initially, New York City graffiti was used primarily by political activists to make statements and by street gangs to mark territory. Though graffiti movements such as the Cholos of Los Angeles in the 1930s and the hobo signatures on freight trains predate the New York School, it wasn't till the late 1960s that graffiti’s current identity started to form.

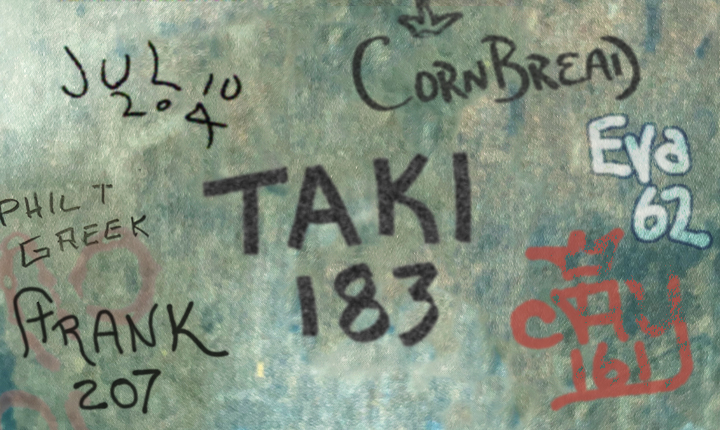

The history of the underground art movement termed graffiti — but called Writing by practitioners — begins in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania during the mid to late 1960s . The motivation was notoriety gained from the volume and visibility of tags. The writers who are most frequently credited with the first serial tagging efforts are CORNBREAD, TITY, PEACE SIGN and COOL EARL. They wrote their names all over the city gaining attention from the community and local press.

Though the Philadelphia movement also predates New York’s, there has been no documentation of a direct connection between the two. It appears that the New York movement started independently. It began around 1967 in the northernmost area of Manhattan with JULIO 204. His name began appearing on streets and subway stations throughout the area. He restricted his efforts to his neighborhood and retired after a short period, but his efforts did not go unnoticed.

PIONEERING 1971-74

Shortly after CORNBREAD and JULIO, the Washington Heights section of Manhattan was giving birth to writers. Inspired in part by JULIO, writers like TAKI, PHIL T GREEK (1), PHIL T GREEK (2), GREG 69 and others began tagging their neighborhood. TAKI was quite prolific. He was employed as a foot messenger, so he was on the subway frequently and took advantage of it, tagging streets and subways throughout the city. The appearance of this unusual name and numeral sparked public curiosity which prompted the 1971 New York Times article "TAKI 183 Spawns Penpals". TAKI was the Greek nickname for his given name Demetrius and 183 was the number of the street where he lived. He was by no means the first writer or even the first king. He was however the first to be recognized outside the newly formed subculture. The Washington Heights neighborhood was a hotbed of activity in the newly forming movement. Early writers include JOE 182, FRANK 136, JOE 136, FRANK 207, TUROK 161, SJK 171, MIKE 171 and JEC *.

On the streets of Brooklyn a movement was growing as well. Scores of writers were active. FRIENDLY FREDDIE, UNDERTAKER ASH and APP SUPER HOG were early Brooklyn writers to achieve notoriety. Movements were brewing throughout the city. Writing started moving from the streets to the subways. The subway system proved to be a line of communication and a unifying element for all these separate movements. Writers in individual boroughs became aware of each other's efforts and the movement became very competitive. This established the foundation of inter-borough competition.

At this point writing consisted of mostly tags and the goal was to have as many as possible. Writers would ride the trains hitting as many subway cars as possible. It wasn't long before writers discovered that in a train yard or lay-up they could hit many more subway cars in much less time and with less chance of getting caught. The concept and method of bombing had been established.

Tag Style

After a while there were so many people writing so much that writers needed a new way to gain fame. Volume alone was not enough to distinguish yourself. The first way was to make your tag unique. Many script and calligraphic styles were developed. Writers enhanced their tags with flourishes, stars and other designs. Some designs were strictly for visual appeal while others had meaning. For instance, crowns were used by writers who proclaimed themselves king.

Tag Scale

The next development was scale. Writers started to render their tags on a larger scale. The standard nozzle width of a spray paint can is narrow, so these larger tags, while drawing more attention than a standard tag, did not have much visual weight. Writers began to increase the thickness of the letters and would also outline them with an additional color. Writers discovered that caps from other aerosol products could provide a larger width of spray. This led to the development of the masterpiece. It is difficult to say who did the first masterpiece, but it is commonly credited to SUPER KOOL 223 of the Bronx and WAP of Brooklyn. The thicker letters provided the opportunity to further enhance the name. Writers decorated the interior of the letters with what are termed "designs." First with simple polka dots, later with crosshatches, stars, checkerboards. Designs were limited only by an artist's imagination.

Writers eventually started to render these masterpieces spanning the entire height of the subway car. These masterpieces were termed top-to-bottoms. The additions of color design and scale were dramatic advancements, but these works still strongly resembled the tags on which they were based. Some of the more accomplished writers of this time were HONDO 1, MOSES 147, LEE 163d, STAR 3, PHASE 2, TRACY 168, LIL HAWK, BARBARA 62, EVA 62, CAY 161, JUNIOR 161 and STAY HIGH 149.

The competitive atmosphere led to the development of actual styles, which would depart from the tag styled pieces. Broadway style (tall skinny letters with serifs) was introduced by TOPCAT 126 who brought it to New York from his visits to Philadelphia. These letters would evolve into block letters, leaning letters, and blockbusters. PHASE 2 later developed Softie Letters”, more commonly referred to as Bubble Letters. Bubble Letters and Broadway style were the earliest forms of actual pieces and therefore the foundation of many styles. Soon arrows, curls, connections and twists adorned letters. These additions became increasingly complex and would become the basis for Style Writing, often termed Mechanical or Wild Style lettering.

The combination of PHASE's work and competition from other style masters like RIFF 170 and then PEL furthered the development of Style Writing. Writers like FLINT 707 and PISTOL made major contributions in development of three dimensional lettering adding depth to the masterpiece, which became standards for generations to come.

This early period of creativity did not go unrecognized. Hugo Martinez, a sociology major at City College in New York took notice of the legitimate artistic potential of this generation. Martinez founded United Graffiti Artists (UGA). UGA selected top subway artists from all around the city and presented their work in the formal context of an art gallery. UGA provided opportunities once inaccessible to these artists. A 1973 exhibition at The Razor Gallery in New York City was a successful effort of Mr. Martinez and the artists he represented. HENRY 161, PHASE 2, MICO, COCO 144, PISTOL, FLINT 707, BAMA, SNAKE, and STITCH were among notable artists in the UGA roster. Media attention began to increase as well. A 1973 article in New York Magazine by Richard Goldstein entitled "The Graffiti Hit Parade" was also an early public recognition of the artistic potential of subway artists.

Shortly after this time period writers like STAFF 161 began to introduce characters, more creative designs and themes to their subway paintings. TRACY 168, CLIFF 159, BLADE ONE and others created paintings with scenery, illustrations and cartoon characters surrounding the masterpieces. This established standards for mural whole cars.

THE PEAK 75-77

For the most part innovation in writing hit a plateau after 1974. All the standards had been set and a new school was about to reap the benefits of the artistic foundations established by prior generations and a city in the midst of a fiscal crisis. New York City was broke and therefore the transit system did not have the resources to fight graffiti effectively. This led to the heaviest bombing (prolific writing) in history.

At this time bombing and style began to further distinguish themselves. Whole cars became a standard practice rather than an event, and the definitive form of bombing became the throw-up. The throw-up is a piecing style derived from the bubble letter. The throw-up is a hastily rendered piece consisting of a simple outline and is sparsely filled in. Throw-ups began appearing all over the system, especially on the IND and BMT subway divisions. Crews like the Prisoners Of Graffiti (POG), The 3 Yard Boys (3YB), Bad Yard Boys (BYB), The Crew (TC) and The Odd Partners (TOP) made major contributions. Throw-up kings of the period included TEE, IZ, DY 167, PI, IN, LE, TO, OI, FI aka VINNY, TI 149, CY and PEO. Writers became very competitive. Races broke out to see who could do the most throw-ups. The trend peaked from '75 through '77, as did whole cars. Writers like BUTCH, CASE, KINDO, BLADE, COMET, ALE 1, DOO2, JOHN 150, KIT 17, MARK 198, LEE, MONO, SLAVE, SLUG, DOC 109 CAINE ONE plastered the IRTs with magnificent whole cars.

.

STYLE REVIVAL 1978-1981

A new wave of creativity bloomed in late 1977 with crews like The Death Squad (TDS), The Magnificent Team (TMT), United Artists (UA), MAFIA, The Spanish 5 (TS5), Crazy Insides Artists (CIA), Rolling Thunder Writers (RTW), ROC Stars, The Master Blasters (TMB), The Fantastic Partners (TFP), The Crazy 5 (TC5) and The Fabulous 5 (TF5). Style wars (artistic competitions) were once again peaking. It was also the last major wave of graffiti before the Transit Authority made the elimination of writing a priority. Crews like TDS, TMT, CIA, ROC Stars were expanding upon styles established by writers like PHASE 2, RIFF 170 and PEL.

LEE, CAZ 2, IZ, SLAVE, REE, DONDI, BLADE and COMET became very competitive in the whole car arena on the 5 line. The UA crew, SEEN, MAD, PJ and DUST dominated the 6 line with elaborate whole cars. MITCH 77, BAN 2, BOO 2, PBODY, MAX 183, and KID 56 ruled the 4 line. FUZZ ONE was a major presence on all 7 IRT lines. CIA, the Crazy Writers (CW), The Boys (TB) and The Kool Artists (TKA) ensured that the BMT subway division was not deprived of creativity.

In 1980, the graffiti removal program, known among writers as The Buff, started up again and pieces ran for shorter periods before being erased. Train yard fence repair was becoming more consistent. Writers slowly started to quit and consider other creative options. Many writers became distracted with thoughts about careers beyond painting subway cars. The established art world was once again becoming receptive to writing.

Graffiti had not received much positive attention from the traditional art world, since the Razor Gallery in the early '70s. It resumed in 1979 when LEE QUINONES and FAB 5 FREDDY had an exhibition in Rome with the art dealer Claudio Bruni. Shortly after, in the early ’80s numerous writers flocked to places like ESSES studio, Stefan Eins' Fashion Moda and Patti Astor's Fun Gallery to explore new opportunities. These and subsequent galleries would prove to be important factors in expanding writing overseas. European art dealers became aware of the movement and were very receptive to the new art form. Exhibitions featuring paintings by DONDI, LEE, ZEPHYR, LADY PINK, DAZE, FUTURA 2000 and others exposed the world to the once secret world of New York's youth.

SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST 1982-1985

During the early to mid 1980s the writing culture deteriorated dramatically due to several factors. Some related directly to the graffiti community itself and others to the greater society in general. The crack cocaine epidemic was taking its toll on the inner city. Due to the drug trade powerful firearms were readily available. The climate on the street became increasingly tense. Laws restricting the sale of paint to minors and requiring merchants to place spray paint in locked cages made shoplifting more difficult. Legislation was in the works to make penalties for graffiti more severe.

The major change was the increase in the Metropolitan Transit Authority's (MTA) anti-graffiti budget. Yards and lay-ups were more closely guarded. Many favored painting areas became almost inaccessible. New more sophisticated fences were erected and were quickly repaired when damaged. Graffiti removal was stronger and more consistent than ever, making the life span of many paintings months if not days. This frustrated many writers, causing them to quit.

Many others were not so easily discouraged, yet they were still affected. They perceived the new circumstances as a challenge; it reinforced their determination not to be defeated by the MTA. Due to the lack of resources they became extremely territorial and aggressive, claiming ownership to yards and lay-ups. Claiming territory was nothing new in writing, but the difference at this time was that threats were enforced. If a writer went to lay-up alone or unarmed they assumed increased risk of being beaten and robbed of their painting supplies.

At this point, physical strength and unity as seen in street gangs became a major part of the writing experience. The One Tunnel and the Ghost yard were the backdrops for many legendary conflicts. In addition to the pressure from the MTA, cross out wars among writers broke out. The most famous war being Morris Park Crew (MPC) vs. the world. High profile writers during these years were: SKEME, DEZ, TRAP, DELTA, SHARP, SEEN TC5, SHY 147, BOE, WEST, KAZE, SPADE 127, SAK, VULCAN, SHAME, BIO, MIN, DURO, KEL, T KID, MACK, NICER, BRIM, BG 183, KENN, CEM, FLIGHT, AIRBORN, RIZE, JON 156, KYLE 156 and the X Men.

THE DIE HARDS 1985-1989

On certain subway lines graffiti removal significantly decreased because the cars servicing those lines were headed for the scrap yards. This provided a last shot for writers. The last big surge on the 2 and 5 lines came from writers like WANE, WEN, DERO, WIPS, TKID, SENTO, CAVS, CLARK who hit the white 5s with burners. Marker tags that soaked through the paint often blemished these burners. A trend had developed that was a definite step back for writing. Due to a lack of paint and courage to stay in a lay-up for prolonged periods of time, many writers were tagging with markers on the outside of subway cars. These tags were generally poor artistic efforts. The days when writers took pride in their hand style (signature) were long gone. If it wasn't for the aforementioned writers and a few others, the art form in New York City could have officially been deemed dead.

By mid 1986 the MTA was gaining the upper hand. Many writers quit and the violence subsided. Most lines were completely free of writing. The Ds, Bs, LLs, Js, Ms were among the last of the lines with running pieces. MAGOO, DOC TC5, DONDI, TRAK, DOME and DC were all highly visible writers. Subway security was high and the Transit Police's new vandal squad was in full force. What was left in the graffiti community was a handful of diehards. GHOST, SENTO, CAVS, KET, JA, VEN, REAS, SANE, SMITH were prominent figures and would keep transit writing alive.

To part 2

Back to history main page

Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.